Simple math tells us that we will not be able to defeat the MAGA Right without enlisting white people in a multiracial coalition. That work relies on and complements Black and POC-led organizing. But which white people do we organize, and on what basis? How do we deal with the white supremacy that runs deep in the veins of this country?

Too often Democratic Party and progressive activists slide by race, aim for the suburban center, and pit organizing white voters against a racial justice agenda. But substantial data and rich history point to the weakness of this approach for the long term. To bring that data and history to bear on the critical 2024 election cycle, the Working Families Party, the Sandler-Phillips Institute, and Showing Up for Racial Justice have convened the White Stripe Project. All three organizations center racial justice and emphasize the strategic significance of voters of color—but argue that white voters have a critical role to play as well.

To illuminate the history today’s “White Stripe” builds on, Convergence turned to organizers who have grappled with organizing white people in multiracial coalitions over the last five decades. Hy Thurman co-founded the Young Patriots, an organization of white Southern migrants to Chicago in the late 1960s – early 1970s. With “Free Huey” buttons on their lapels and Confederate flags on their jackets, they joined the Black Panthers and the Young Lords in the first Rainbow Coalition. Hy now heads the North Alabama School for Organizers. Carla Wallace organized in Kentucky for Rev. Jesse Jackson’s 1984 and ’88 campaigns. She worked in the Louisville area, with LGBTQ people electrified by Jackson’s support—unprecedented for any presidential candidate—and also across the state with farmers, miners and other rural Kentuckians. Carla went on to co-found Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ) in 2009, sits on the organization’s board, and organizes with its Louisville chapter. Beth Howard is the current Appalachian People’s Union director for SURJ, organizing in rural eastern Kentucky. Organizer and filmmaker Eddie Wong, who served as the national field director for Rev. Jackson’s 1988 campaign, moderated the Dec. 12, 2023 conversation. Additional material comes from a Dec. 15, 2023 interview with Hy Thurman by Convergence Print Editor Marcy Rein.

Eddie Wong: Let’s start by talking about the communities where you did or are doing work. Can you paint a little picture of the place to help frame things?

Hy Thurman: I moved to Chicago when I was 17 from Dayton, Tennessee, a very small rural town. I had a brother that lived in Chicago. There were over 40,000 people [in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood] at that time, which was in 1967. There were some Native Americans there, Hispanics, very few Blacks. It was mostly Southern white. We were subjected to all kinds of conditions. Women were being raped by the cops. People were being murdered by the cops. We were the first to be drafted. There was no health care. No food pantry, no jobs. Slum living. Some people were actually starving.

I had to go to work at a day-labor agency where you would get to work for one day if you were lucky. And you’d have the worst jobs because you didn’t have any union representation. A lot of people were actually injured on the jobs, or injured so they couldn’t go back to work again. Right next to almost every day-labor agency was a blood bank. That was a facility where you can sell your blood, and that’s how some people supplemented their income.

Carla Wallace: The organizing I do today with SURJ was very much informed by the work in the Jesse Jackson campaigns of 1984 and ‘88. With Kentucky being among the poorest states in the country and one of the whitest in the South—the Black population and people of color population still hovers around 13% statewide—it means there’s no way to shift things without listening to and speaking to the pain of struggling white folks. So poor and working-class white communities in Kentucky were a part of who we were working with. In Louisville, the Rainbow Coalition effort was anchored by the Black community. The white base part of it, or the white stripe, was cross-class, but it was focused on white workers, especially union workers in Louisville’s South End, white families that needed health care, students who were struggling to find jobs and pay off loans, and others on the margins.

Too often, candidates are told to “play it safe to win.” But Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition was about taking on what mattered to people. Jackson was the first presidential candidate to come out on the pariah issue of equality for LGBTQ people. The roots of that came in part out of Louisville, and our struggle around LGBTQ equity in the 1980s. In 1988, Jackson became the first presidential candidate in history to attend a national rally for LGBTQ justice in DC. I was newly out and it was my first demonstration on that basis in Washington as well.

Beth Howard: SURJ is prioritizing working-class white people, and Southerners. We organize that specific base because we know that those are the white people that have the most to gain from a multiracial coalition fighting for racial and economic justice. I organize where I’m from, rural eastern Kentucky and central Appalachia, an area that’s even whiter than the state as a whole.

Our priority project is the Kentucky People’s Union, in and around Ashland. The area is growing and becoming more diverse, just as KPU is growing and becoming more diverse. In our first photo that we have, at our first community meeting, we were 12 out of 13 white people. And in a photo from a year later, after we’d been organizing, bringing people into the group and building relationships, we have 50 people and the group is multiracial, all ages, and many different identities and life experiences

Eddie Wong: What issues and common concerns have helped build multiracial work?

Hy Thurman: As a young group. five or six of us actually went out and organized a march on the police station. After this first encounter with the police, we marched on the police station with a couple hundred people. And that was also Hispanics and American Indians, a few Blacks—there weren’t that many in the community. And you know, Southern whites. After we did that, all hell broke loose and cops came down on us again, and they murdered one of our members….

We wanted people on welfare to quit being treated like animals. So we went down and took over a welfare office and got some policies changed. We took over a hospital clinic that belonged to the Board of Health because they weren’t treating people the way they were supposed to. They only put their Board of Health Clinic in because we started the Young Patriot Clinic, but that’s where we started organizing.

We worked on a number of different projects with them [the Black Panthers]. When they would have rallies we would go and the Young Patriots would serve as security, and we would serve them on planning. Course we were concentrating at that time on our health clinics, medical clinics, breakfast for children programs in which we are all working together. And they were helping us get the resources for that. They were also working on buying buildings in their poor communities. That’s when Freddie Hampton was assassinated, so a lot of it didn’t go through.

We were in court with them fighting the city tooth and nail when they were trying to close down all of our clinics and our breakfast for children programs. We were all working in tandem with each other on these problems within our communities.

Carla Wallace: Much to the shock of the national and local Democratic Party, in 1984 we won the Third Congressional District, which was largely Black, but then we also won the overwhelmingly white Fourth Congressional District. We won because if you know how to organize, you know how to win caucuses. You just knock the h-e-double “l” out of the doors and you get people there.

People were excited by Jackson’s candidacy, what he stood for, and they just needed support to engage the process. The Democratic Party saw that writing on the wall and did away with the caucus process in Kentucky and most everywhere else as well after that. But even though they changed the rules, and it was a general primary in 1988, building with the leadership of Black Louisville and whites with a clear stake in peace and justice, we were able to win the Third Congressional District again as part of Super Tuesday.

We were also organizing statewide. For decades in Kentucky and other states with large rural white populations, consultants and Democratic Party leaders would say “no, you can’t bring race into the conversation or you will just divide people.” But we knew we had to bring race and economics together….

Not since Kennedy in 1968 had a presidential candidate visited Eastern Kentucky. But when Jesse Jackson spoke in the Hazard gymnasium in early in ‘88, the huge, largely white-mining-family crowd went wild. He told them, “When the lights go out in the mine, no one knows what color anyone is.” And they roared as he pointed our anger at the coal bosses instead of each other across the racial lines.

When the lights go out in the mine, no one knows what color anyone is.

—Rev. Jesse Jackson

I was reporting on the event for a national progressive paper, and I asked a number of people why they were there for Jackson. And they said, “I know he’s Black, but he’s speaking to what we’re going through.” Jackson’s rainbow agenda, plus the ground organizing that we did, added up to kind of a glimpse of what a cross-race working-class alliance could look like in Kentucky and other parts of the country too. That was incredibly hopeful and exciting for me as a younger organizer at that time.

Beth Howard: KPU started with what we call a listening campaign, where we went door to door throughout the community, talking to people and asking them, “What do you love about living here? What do you want more of, but also what are the problems?” What we heard over and over from working-class people–white, Black and Brown–was economic justice issues, primarily people having difficulty paying their rent, finding a place to live, a job that pays a living wage, that has health insurance and benefits, difficulty accessing health care, paying for medicine, getting to go to the doctor, and also the impacts that we’re still feeling from the overdose crisis. After hundreds and hundreds of conversations, we came up with four problem areas that were the most prevalent: lack of affordable safe housing, the overdose crisis, lack of access to quality healthcare, lack of good-paying, safe jobs.

We voted and we chose housing as our issue campaign. Right now we’re working on a campaign to win a Tenants’ Bill of Rights, which would be a package of ordinances that will be passed through the city council to make housing more safe and affordable for the residents in Boyd County.

Eddie: So you’re finding common ground on the economic issues, but you’re also battling historic ideologies of racism and white supremacy. How do you reconcile those things in your organizing?

Hy Thurman: Some of the people that came along to work with the Young Patriots couldn’t handle it. They were still very, very, very racist. Eventually they had to be kicked out, or they would leave because it was hard.

We tried to reach racist people by using a racist symbol. We wore the Confederate flag with a free Huey button or something from a Third World country or Martin Luther King or something like that next to it, and it would spark up conversation.

—Hy Thurman

We tried to reach racist people by using a racist symbol. We wore the Confederate flag with a free Huey button or something from a Third World country or Martin Luther King or something like that next to it, and it would spark up conversation. It was a contradiction. And so we were able to talk to people who were racist. people that were in the Klan and other groups.

There was a man that was a Klan member, and I got into a conversation with him about the flag and all it represented, and why we would wear it with a Free Huey button or whatever. And I asked him, “Okay, what if you had a child that was dying?” And he did have children. And I said, “What if your child needed an organ transplant or that child was going to die? And all of a sudden, it became available, but it belonged to a Black person. Would you take this organ to save your child’s life?”

Without hesitation, he said, “Yes.” And I said, “What’s the difference? What are you looking at? We’re always seeing just the colors, and how society has treated us as different and how society has taught us that we’re white and we’re superior, you know?” And so he got it. Eventually he got it. He brought his kids to our clinic.

Beth Howard: Economic issues can get us in the door, but then how do we grow and transform and how do we understand that everything that we want to win materially is going to depend on white working-class people being in strong solidarity with Black and brown people? We try to use our history as political education to keep bringing people along and to talk about race directly.

We’re organizing in the heart of Appalachia, and we have a long, long history and legacy of some of the most powerful multiracial organizing in the country when we look at mine workers organizing. One of our inspirations with the Kentucky People’s Union is the miners who were in the Battle of Blair Mountain.

The battle of Blair Mountain was 10,000 miners, multiracial immigrants, largely Italian immigrants, Black miners and poor white miners, who came together in the largest labor uprising in this country’s history fighting coal bosses and their hired gun thugs for the right to unionize.

One of the coal barons during the years of the West Virginia mine wars was Justus Collins, and he was very open about the way he structured his mines and mining town. He set up his mining housing so that a third were white miners, a third were immigrants and a third of them were Black. And he did that on purpose because he thought the cultural differences, the language barriers, and race would keep them fighting with each other and they would never have enough commonality to overcome that and to unionize.

But the good organizers of the Industrial Workers of the World and the United Mine Workers of America came in and brought the miners together so that at the peak of this conflict in this uprising, there were 10,000 of them, and they wore red bandanas so that no matter where they were, no matter if they had language barriers or cultural barriers, they could see that bandana and know that they were in solidarity.

And so we wear red bandanas around our necks and this is a symbol of unity. We use these stories and this history as an example of the best of us. I don’t want to paint this history as if that was a perfect, utopian time. It absolutely was not. However, it was also remarkable, right?

One of the things we know, too, is that when we can get people in the door by organizing around housing or a material condition, and when we ensure that group is multiracial, people do start building relationships with one another, and that’s how I believe we change our hearts. And I’m not sure those relationships would happen unless we were working on something that brought people in with a very clear self-interest, and then that self-interest becomes a shared interest of the group.

Carla Wallace: The Jackson campaign gave us a lot of lessons around what organizing at the intersection of racial and economic justice could look like. Jackson used to say, “We’re moving from the racial battlegrounds to economic common ground and on to moral higher ground.” None of that was ever about hiding the way white supremacy divides us. Jackson gave people something to believe in, an agenda that put people first.

At the time we were in the midst of the impact of the Reagan tax cuts to the rich and doubling the military budget at the expense of the poor. Back then and today, when you talk with white folks who are hurting, people know they’re hurting. They also know that somebody else is benefiting at their expense. When we don’t talk about race, we leave a hole the size of a mountain for the other side to plow right into. The other side is not afraid to talk about race. They’re not afraid to talk about trans issues. They’re not afraid to talk about abortion. We avoid those issues at our peril.

As the US-funded death toll in Gaza rises, I’m remembering Jesse Jackson as a presidential candidate unafraid to talk about cutting the military budget in order to fund schools and housing and jobs. Jackson pledged no-first-strike to keep the US from being able to initiate a nuclear war. Jackson was not afraid to support peace with justice for Palestine.

The movement was much stronger and more intentional then in connecting the issues of militarism and war to why we didn’t have what we need to take care of people at home. It is critical that we get back to making those connections today, and the Jackson campaign gives us a lot of lessons on how to do so.

Eddie Wong: We have serious challenges in fighting MAGA in the electoral arena. People are so alienated from politics in general and then Biden’s not helping us any. How do we fight the disaffection and then how do we organize if we if we are not able to succeed?

Hy Thurman: In electoral politics, if I didn’t put anything on Facebook anymore about Trump, somebody would come back and say, “You sound like a Democrat.” If I put something about Biden, they come back and say, “You sound like Trump,” and that’s how divided everything is. To me, they’re just Republicrats, they’re both the same. And that’s the point we’re trying to get over but we’ve got a long way to go. We got a lot of white supremacy out there. You still have the MAGA supporters. We still have Nazis, but we can’t let that scare us. We have to keep going.

The North Alabama School for Organizers, we have joined down with the Poor People’s Army. We will be organizing nationally, to get people to come to the DNC and RNC conventions. We hope to have a massive rally at each of these to try to get the message out as to what the masses of the poor people are going through…. we also will have classes, on fascism, organizing and inviting people in, you know where they are.

I still respect my one of my mentors, Fred Hampton, and I still read everything that I can about him and try to continue his legacy. He always said, “We have to be boots on the ground.” Those boots have to be real. They ain’t stilettos. They’re not any of these other important, expensive boots, but we got working-class boots. And those are the ones that we have to put down on the ground. That’s what the working-class people have to see.

Beth Howard: At SURJ we talk about having a block and build strategy, and that we need both. Blocking is our electoral work, blocking a MAGA takeover. And so we are doing electoral work as an organization in Wisconsin, Georgia, Ohio, North Carolina, and Arizona, and we are focusing on a strategic sector of working-class white people. The work that I do in the Kentucky People’s Union is part of that build strategy, where we are going out and building the thing we need to win long-term. And sometimes those two strategies overlap, our block and build, such as KPU building a base around a housing campaign and running our members for city council so we are governing, too.

Kentucky often gets labeled a red state, but what I like to tell people is we’re a low voter turnout state. Our voter turnout in 2023 was only around 38 percent. And of course, that is because we have so much voter suppression and also because we live in a place where over and over elected officials, politicians, have shown up and made us promises they never delivered on.

I’ve heard Carla say about the Jackson campaign that he did show up and he did care, and I have seen that too. We just reelected our Democratic governor, Andy Beshear, and Eastern Kentucky went blue at the top of the ticket. People were willing to vote for a Democratic governor, even if they voted Republican all the way down the rest of the ticket and were registered Republicans. We called thousands of voters. The number one reason that rural working-class white people were voting to reelect Andy Beshear is because of the flooding and climate catastrophes that hit Eastern Kentucky, because he showed up and delivered relief, and because of COVID relief. Andy Beshear’s response during COVID was one of the best governor responses in the entire country.

This shows Kentucky values those values we talk about: that we care for each other, we have each other’s backs. And while any elected official is imperfect, Beshear’s re-election was also important because he is a governor who called trans kids “children of God” and who stood up unquestionably for abortion rights.

It’s not that people in Appalachia don’t believe in the government. We want to believe in a government that we see actually do something for us and that works. We want to see somebody care about us and then put some actions behind that. When we have candidates that do that, we can use electoral organizing as power building and we can elect people who give a damn about us.

We want to believe in a government that we see actually do something for us and that works. We want to see somebody care about us and then put some actions behind that.

—Beth Howard

One of my mentors, Jerome Scott, who was a co-founder of Project South and a leader in the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, would say we have to take every opportunity that we can to talk to working-class people, and electoral politics is one arena and we can’t leave it off the table. And so I have that mindset even when I’m not excited about it. This is one way that working-class people are thinking about politics and about issues that are happening in the world, and I’m going to take that opportunity to knock on their door. To pick up a phone and call them.

Carla Wallace: Part of what I learned in the Jackson campaign was—and for folks who were in it this was a very hard conversation—was that all that energy that got generated and all those people mobilized through electoral work, was not directed into an ongoing organizing project that we could sustain and build on in the years since. We tried to move the electoral gains into intersectional multiracial organizing, but we didn’t have what we needed to make it sustainable. I don’t put that on Reverend Jackson. It’s an ongoing challenge on the Left and the progressive movements that we’re still grappling with today. I think it comes back to us being clear that our overall goal is building multiracial power for collective liberation, for real democracy. When we are grounded in that, then everything we do, and how we do it, can add up to getting there.

I see everything through the lens of how we build people-power. That people-power has to be anchored in those communities that most need what this system can’t give us: health care, housing, jobs, a cleaner earth, community, public space, peace. I’m not fixated on there only being one way to do that, but I am fixated on what works.

Direct action, street protest, building alternative institutions, even community organizing and electoral work are only good and right for the moment if they are building what we need to be stronger than the other side. To be able to take care of each other in the face of a system that doesn’t, and eventually gain the governance that is needed to win the world we deserve, we need a lot more power than we have now. I’m all about building that power—multiracial power. It’s going to be led by a Black vision for the world we need and it’s going to be in multiracial coalition. There is no way we will have the numbers we need if we are not organizing the white stripe of this movement for liberation. And that piece—that is on those of us who are white.

Beth Howard: One of the things that I take away about working with working-class white people, especially in Appalachia, is that we are a group of people who have been called trash, white trash, hillbillies. So I think that one of the most important things we can do is treat people with dignity and respect, like they matter, and just show them love and to help them feel and know that they are inherently worthy, and that they are needed. Largely in movement, in progressive spaces or liberal spaces, we’re not welcome. We’re usually the butt of a joke, right?

That has got to change–and not just the attitude, but actually creating a group that is built by them and that is for them. That is my hope in creating the Kentucky People’s Union and our other projects that are rooted in grassroots organizing in Kentucky and Appalachia. This is the group that I wish my family had.

I am very proud and grateful to be in this legacy of the white stripe of the Rainbow Coalition, that I’ve been carrying on in the tradition of those who have gone before me, like Hy and the Young Patriots, our ancestors from Blair Mountain and people like Anne Braden and Carla and other people who have taken on this task of organizing working-class Southern people. And I think that every time I knock on a door, every time I pick up a call, it brings me closer to them, so I’m always carrying that with me.

Carla Wallace: The struggles that have gone before us are so important for us to lift up—not just what they accomplished, for our wins are too few—-but the journey of struggle. Sometimes we can be in a struggle and it can feel like this is the hardest it’s ever been. I get great hope seeing that up against the odds, over and over, people have resisted and will continue to resist, will continue to fight for change. We’re showing up for ourselves and for each other and that gives me hope when it feels so uphill and so hard.

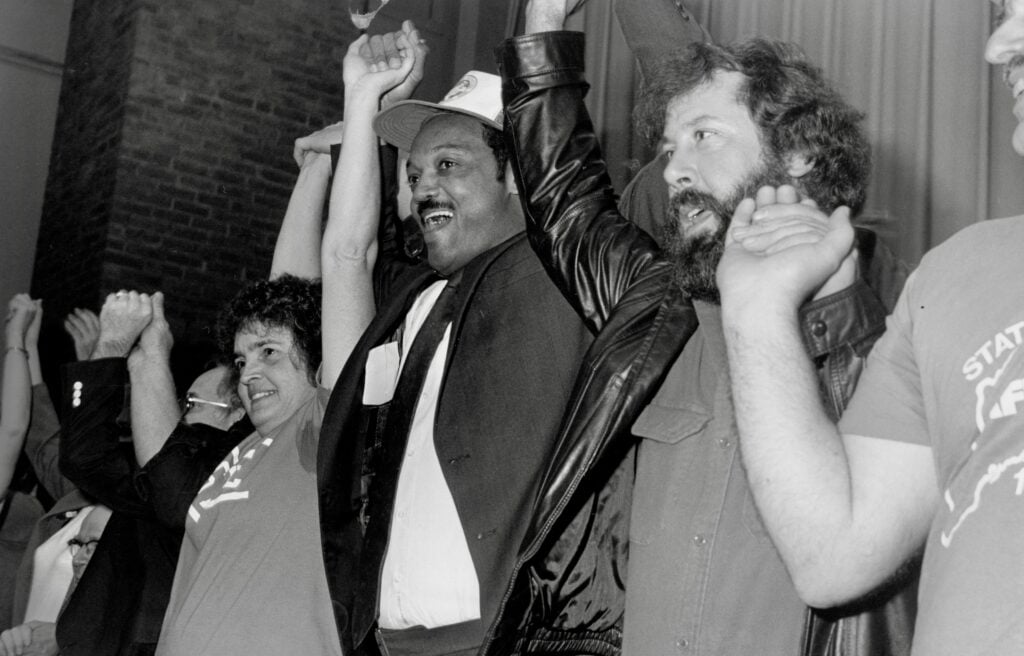

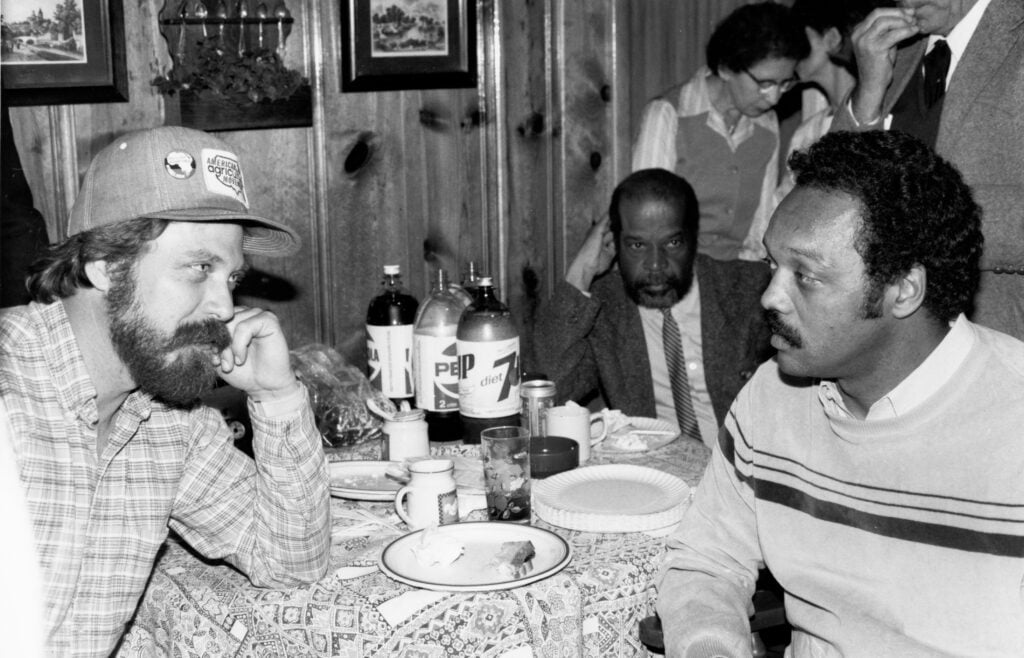

Featured image: Rev. Jesse Jackson with striking International Paper workers in Jay, Maine, October 1987. Photo by Rick Jurgens from the Unity Archive Project.

A longer version of this conversation appears on East Wind E-Zine.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.