Bishop William J. Barber II is a long-time organizer and co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. In Smithfield, North Carolina he was key in fighting a racist poultry plant boss who called I.C.E. to threaten unionizing workers with deportation. As head of the North Carolina NAACP in 2013, he helped pull together a multi-racial coalition of mass organizations for “Moral Mondays,” civil disobedience actions targeting the North Carolina state legislature. Since then, the Moral Monday campaign, in which he continues to play a leading role, has mobilized over 2,000 people on a weekly basis for mass sit-ins to win progressive policy demands.

Bishop Barber looks to the First Reconstruction as a model for waging our present struggle, observing that inequities which the First Reconstruction sought to eradicate still structure our society today. Ezra Kaprov recently sat down with Barber for a historical analysis of Reconstruction as a guide for strategy. Following the Civil War, a multi-racial progressive united front fought a series of battles to maintain a balance of power between themselves and the Southern aristocracy who wanted to restore the slave system. Before surrender was even signed, the defeated confederates formulated contingencies for holding onto power and continuing to assert their will.

Ezra Kaprov: In Black Reconstruction in America, W.E.B. Du Bois details a shift in the balance of forces following the Civil War, between the old Southern aristocracy and the masses of former slaves together with poor whites. The Poor People’s Campaign uses a Reconstruction framework to analyze possibilities for enacting another such transformation today. Can you talk about the sort of fundamental changes accomplished during the First Reconstruction?

Bishop William J. Barber II: When you use the language of reconstruction as a framework for looking at the process of social transformation, you first have to know the history. The First Reconstruction began in 1865 at the end of the Civil War. The Reconstructionists built moral fusion coalitions made up of Blacks, both free and former slaves, and progressive whites. They carried a vision rooted in our deepest religious values as well as our deepest constitutional values: establishing justice, providing for the common defense, and promoting the general welfare. They were saying, “It’s time for these lofty principles of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness to apply to all people.”

Thanks to them, by 1868 you have the passage the 14th Amendment, which actually saved our democracy, because it said not only have we ended slavery: We’re now saying equal protection under the law is a right of all people, not citizens, but all people within the boundaries of the United States. That one amendment was a critical victory of Reconstruction because it meant that everything in our Constitution—the right to privacy, the right to free speech, the right to a trial by jury—none of those things can be denied on the basis on skin color as they had been up the that point.

Then by 1870 they secured passage of the 15th Amendment, which says that no state or entity can deny or abridge the right to vote. Now having the word “abridge” there is interesting language because it means you can’t remove the things that have already been done to ensure the right to vote is extended. There was power in that Black-white fusion coalition having won both equal protection under the law and the right to vote. Now a weakness of Reconstruction at that time was that this didn’t apply to women. That wouldn’t be won until later.

The Reconstructionists in 1875 won the passage of a civil rights act which in essence makes racism as a policy matter federally illegal. And also by that time, every Southern state constitution has been rewritten to take out any vestiges of slavery. In fact, the preamble to North Carolina’s constitution was rewritten to include all persons having the right not only to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but also to “the enjoyment of the fruit of their own labor.”

The First Reconstruction was roughly from 1865 until the early 1900s. Its final vestiges were undone during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency after he played the film Birth of a Nation at the White House in 1914—a film celebrating the Ku Klux Klan, who sought to “redeem” the country from Reconstruction and “make America great again.” The film demeaned Reconstructionists as Black and white people who took from the country. Wilson declared that this is history which needs to be taught and he made that a centerpiece of his administration.

He began backsliding on the promises he made to promote racial justice. He lied and blamed the Spanish people for the 1918 pandemic, calling it the “Spanish flu.” He sat by as white supremacists unleashed targeted riots against Blacks in city after city during the Red Summer of 1919. There was a total retrogression of all the victories that had been won in the first Reconstruction and it manifested in mass anti-Black violence. By 1920 Black men were being lynched daily.

EK: How does a Reconstruction model seek to combat the particular violence of white supremacist power relations while cracking the foundation of all social, political, and economic oppression?

Bishop Barber: Reconstruction is a model of building a society in a way that there is more access to rights by those who have been historically denied. It’s a model that says you have to be guaranteed the right to vote, you have to be guaranteed equal protection under the law, you have to be guaranteed basic access to education, and you have to be guaranteed justice in the courts. These are things that ought to be fundamental rights of which Black people in America had been long deprived. That was a result of policy racism at every level, from the municipal to the federal.

Reconstruction is a model of building a society so that there is more access to rights by those who have been historically denied.

Reconstruction begins with questions about what is being denied which ought to be a fundamental right. What is it that racism is denying to Black people? What is it that classism is denying to poor and working people? And how then do you shape public policy so that the few cannot rule over the many? That’s what we in the Poor People’s Campaign mean to ask using a Reconstruction model today. What are the policies which enable poverty to the extent that now 43% of all people in our nation live in poverty?

Reconstruction says, “We’re gonna take every piece of public policy and we’re gonna lay on top of that policy the great moral promises of the Constitution and our deepest religious values.” It’s a much deeper way of examining public policy. Then it’s about codifying these matters of public policy at a federal level so that they apply across the land. Importantly a Reconstruction model is honest about the past, and honest about the failures of the past.

But it goes beyond this policy or that and says society has to literally be “reconstructed.” In other words, you can end slavery, but if you still have policy racism and the denial of voting rights, then you still don’t have a society in which the uplift of all people has been made possible. Reconstruction occurs as a series of battles, not merely for policy change, but for the soul and the future of our nation.

The Declaration of Independence says the duty of the people is to “alter or abolish” (or reconstruct) their government when it’s acting in a way fundamentally contrary to the nation’s moral principles. The crisis of democracy we’re facing now, which is also a crisis of civilization, is exactly the situation illustrated in that text. We need a Third Reconstruction to alter our government in the direction of a moral realignment, so that everyone benefits and not just some.

EK: Can you speak to the explicitly moral grounding used by the Poor People’s Campaign in crafting the model for a Third Reconstruction?

Bishop Barber: The approach to social transformation using a Reconstruction model has a few basic pieces. You have moral analysis, where you examine public policy through the lens of our deepest moral values. Then you have moral articulation, where you talk start talking about the problems of society in moral language and not mere partisan language. And then you have what we call moral attention, where you begin putting a face on negative realities, so that the 140 million people impacted by poverty in this country aren’t just numbers.

Finally, you have moral activism which, whether you’re looking at the First Reconstruction of the 19th century or the Second Reconstruction of the 1960s, means you’re willing to go all out in any way nonviolently to change the prevailing the reality. If that means nonviolent civil disobedience, you do that. If it means mass protest, you do that. If it means mass voting, you do that. But you only do all that after first undertaking a moral analysis, engaging in moral articulation, and calling moral attention.

EK: After the Civil War, multi-racial progressive coalitions leading state governments in the South resolved to fund the newly founded Freedmen’s Bureau–a public institution tasked with dismantling the old Confederacy–through a policy of taxing former slave owners. In Du Bois’s words, the nature of these taxes “amounted to confiscation” of the aristocracy’s land and property. Why was confiscation necessary and how does taxing the rich remain a core pillar of the Reconstruction framework?

Bishop Barber: What Du Bois was attempting to help people understand with that passage about confiscation was that the poor, and in particular the Black poor, had already been taxed. Still today poor and low-wealth people are already over-taxed. Prices for goods and services are often much higher in low-income areas, not to mention sales taxes.

The Southern elite taxed human beings with free labor and then benefited from that. He’s saying, you can’t build wealth off the backs of others and then argue that laws, in this case tax law, can’t be used for uplift of society, especially when you’ve already used the laws to ensure that so much of society has been held down. It’s interesting to me when people push back against taxing the wealthy or making up for past injustices. I think it’s an attempt to forget just how much wealth has been accumulated from those injustices.

When Dr. King talked about the redistribution of wealth, some saw that as a negative thing. But in the history of the country it’s clear: there’s been a massive redistribution, it’s just always away from the people whose labor actually produces the bulk of the wealth and towards the top. When a CEO makes more than 300 times the salary of his average worker, that’s redistribution of wealth.

There’s no genuine democracy when there’s an ongoing distribution of wealth upward and away from the people. Right now in this country we have 400 families making an average of $95,000 an hour and three people own more wealth than then bottom 50% of the American population. Du Bois was right and Martin was right: there’s an unjust distribution of wealth. A Reconstruction model says to challenge that.

When we say, “Pay people a living wage, give them guaranteed healthcare, and guaranteed labor rights,” we’re demanding a stop to the wrongful redistribution of wealth and to allow for the proper distribution of wealth. That’s how we can promote the general welfare of all people. And according to our Constitution, that’s a necessary pillar for a functioning democracy.

The wealth that’s been created through slavery, through Jim Crow, and through the denial of living wages is a form of theft made possible by misusing the levers of government to rob people in broad daylight.

EK: Du Bois emphasizes that the establishment of public education, and even the replacement of chattel slavery with wage labor across the South, was only possible because in 1870 Black American men won the right to vote and hold office. Working people, Black and white, were then able to use their numbers at the ballot box to enact progressive policy change. What does that suggest for us about the centrality of racial justice in defending the vote?

Bishop Barber: To go a bit deeper, Du Bois would never limit those victories as being only the result of the Black vote. He was a Reconstructionist, which meant that he understood that Black folk alone couldn’t transform the country to a genuine democracy. A Black-white fusion movement, that’s what really changed the South. It was former slaves, freedmen, and poor whites who came together, all of whom had been held down in different ways by the Southern slave aristocracy.

The aristocracy kept Blacks enslaved, but they also kept down wages for poor whites. They didn’t allow Black men to vote, but they also didn’t allow white men without land to vote. The aristocracy made sure their sons didn’t go off to war, and so the war for the Southern side was fought by poor whites. The genius of the First Reconstructors was that they figured that out, and they put the pieces together to realize their common predicament. Reconstruction was done through a Black-white fusion coalition, not Blacks alone.

We should never separate, for example, the battle for voting rights from the battle for living wages, or the battle for healthcare.

The civil rights community in this country made a grave error nine years ago in not waging a bigger fight when the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act. One study shows that 55 million Americans who voted in 2020 won’t have access to the polls in 2022. And yet, how many Democrats railing against Trump and “the big lie” are willing to make voting rights a central part of their campaign platform? Even those who do often make the mistake of only having a Black audience. Really they should be building coalitions of Black people, indigenous people, white people, and poor people generally because the attack on voting rights is an attack on democracy itself.

That said, as Du Bois notes, it’s also an attack on progressive economics. We should never separate, for example, the battle for voting rights from the battle for living wages, or the battle for healthcare.

What the Poor People’s Campaign is doing is not just talking to Black folk, but also to poor white folk in Appalachia, in Alabama. We go to them and say, “The people who repress democratic rights for Black folk are the same ones who vote against you having living wages and healthcare.”

They want to suppress the Black vote, yes, so they can unleash their policy agenda. But it’s not just about stopping Black people from voting, it’s about them having power however they can get it. Never again should we talk about voting rights as though it’s just a Black issue. It’s a democracy issue. It’s also an economic issue, because whoever gets the votes also controls the dollars in our government’s budget, as well as making the economic policies that impact the lives of everyday people.

The Poor People’s Campaign is organizing a “Mass Poor People’s & Low-Wage Workers’ Assembly” on June 18, 2022. More information here.

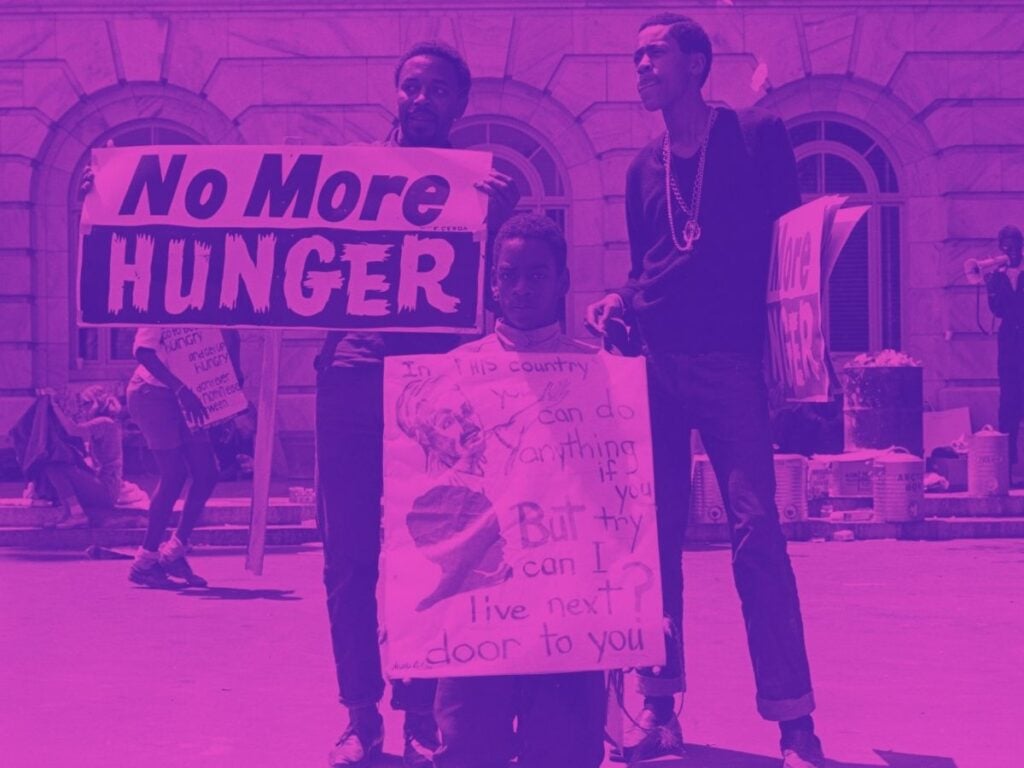

Featured image: Poor People’s Campaign demonstrators in Washington, D.C. in 1968. Via Georgia State University from Southern Christian Leadership Conference Records in the Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Emory University

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.