Gloom shrouds the news on the economy. Workers get blamed for inflation and the common solutions on offer bring more pain. But when we center the interests of workers and communities, we get a different picture of the causes and cures for our economic woes. While wage increases can contribute to inflation, they don’t have to. Corporations can absorb higher wages by cutting profits or CEO salaries, for example. In fact, the increases in workers’ wages have barely brought them up to pre-COVID levels, while CEO pay and profits have increased exponentially. And there are other key sources of inflation such as energy prices and supply chain issues, that are more significant than wage increases.

The Federal Reserve, usually presented as a gray eminence above the fray, actually plays out a distinct neoliberal agenda—one that sees higher unemployment as an aid in disciplining the workforce. Raising interest rates is far from the only answer to inflation. Investments in clean energy could help bring down fossil fuel prices, for example; targeted policy interventions could help un-kink the supply chain. And powerful people-centered movements could rein in corporate power.

Our new series, “People-Side Economics,” will expand on these perspectives, exposing the bias and half-truths we hear every day, and bringing ideas we can use in organizing. In this fourth installment of the series, Heather McGhee—author of The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together—speaks with Convergence editorial board member Stephanie Luce.

Stephanie Luce: As we assess the midterms, and as we think about the coming year, what should organizers know about the economy? For people who aren’t experts, how can they make sense of what the economy is?

Heather McGhee: The first thing I always say is, the economy is not the weather. It’s not a series of unexplained, uncontrollable forces that we just have to protect ourselves from and prepare for. The economy is more like a game. And there are rules of the game. And the most powerful players are the ones who write the rules and who rigged the rules.

And so often, how often you succeed, how you score, how many points you score, has a lot to do with your individual effort and skill, absolutely, like in any game—but also, it really matters what the rules are, and in whose favor the rules are skewed. And it matters a lot what team you started out on. That’s really important for organizers to understand, and for organizers to share with others because we have some really skewed mental models about what the economy is.

The other thing I’d add is that whenever we are storytelling about the economy, it’s important, whenever possible, to find a powerful corporate interest to lay blame on because the default in most of our dominant economic narratives is to blame either inexplicable natural forces, government or individuals. And corporations often get off scot-free.

When we’re talking about things like inflation, for example, we should be talking about record corporate profits, not acting as if inflation is just like some balloon that just sort of rises up on the wind. There are corporate executives who are setting those prices. And they’re doing so because they have the power to price-gouge due to the pandemic, and due to a lack of competition from small business.

So, whenever possible, find a corporate actor. It’s not that hard to do. You know, inflation is something that is covered on a daily basis in media markets around the country. And yet very few people are looking at record corporate profits. It’s just right there, hiding in plain sight.

SL: That is very useful. What kinds of solutions should organizers be fighting for? How can we make things more fair?

HM: I’d say that when you’re trying to create a multiracial coalition, you need to try to offer up a win-win solution, where it’s clear that we can win more together than we can apart. I call these solidarity dividends––these gains that we get from recognizing that there are common solutions to our common problems. That is not to say that every community is suffering exactly the same because of course, it’s not true. And today’s racial economic divides are largely the product of explicitly racist history in the 20th century. It’s where history shows up in your wallet, particularly for Black and Brown families. But given the same kinds of public investments that helped build a white middle class, Black and Brown families would be able to succeed.

Today, a Black college graduate has less wealth, on average, than a white high school dropout. That statistic is helpful because it tells us that it’s not just about hard work and income and the normal measures of success that we think about, but rather it’s about history, right? It’s about interest being paid or interest being earned on explicitly racist decisions to, for example, lock Black families out of homeownership for generations, which is what the government and banks colluded to do on a never-substantiated assumption that black people will be too much of a credit risk. And the same with job discrimination and educational segregation, and the destruction of black wealth, often for reasons of urban renewal and highway construction.

Any story about the economy that doesn’t include a discussion of power is incomplete. If you think about that game analogy, it’s about who has the power to change the rules. And so, we should really be wary of storytelling about the economy that focuses too much on individuals. And that doesn’t give you an analysis of who’s profiting off of this economic situation. And how do they have the power to exploit workers, or families, or consumers, or the environment?

SL: A lot of people are intimidated by economics and worry they are not qualified to talk about it. Can you talk a bit about how your approach, which involves storytelling, helps make it more accessible?

HM: Yes. I think being able to look for the corporate villain is helpful, because organizers understand that, right? They understand targets, they tend to understand that kind of story well, because storytelling is such a fundamental building block of organizing. And so just remember that you don’t have to have a lot of statistics, what you have to have is a memorable story. And so you can tell a story of a worker, and how their employer spent more money manipulating their stock price than they spent in wages. Talk about what that meant for the worker and her children, and what that meant for the tax base of her community. That’s the story. You don’t need to know a lot of macro-economic statistics. You can really personalize it.

SL: You gave a lot of those kinds of great stories in your book. People should read the book! But do you have a few key ones that you could share?

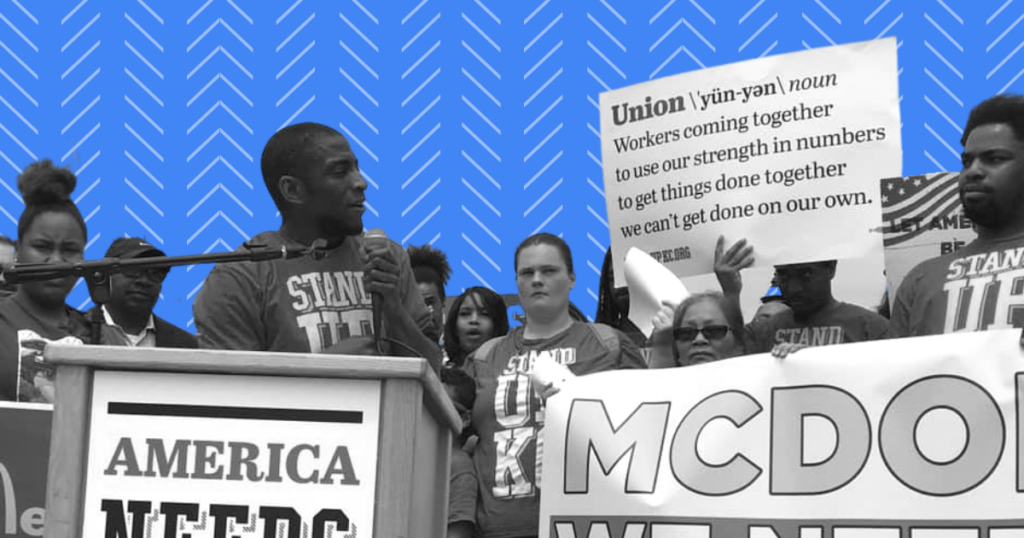

HM: I think the story of Bridget and Terrence in the labor chapter of the book is helpful because it speaks specifically to organizing and how there was a shift of consciousness for both of them. Both are fast-food workers in Kansas City. Terrence is Black and Bridget is white. Both of them went from blaming themselves or other workers for their working conditions to putting the blame where it belonged, on the corporations that paid starvation wages. And then they realized that it was only through collective action that they could have enough power to change the rules. They came together in the Fight for $15 movement to put pressure on the boss to raise wages in their state. So that’s a good sticky story, where the solution is collective action.

I think the story of the drained pool is helpful for people to understand how we got to this place where there’s so little, by way of public goods, that you can be proud of. I tell the story of how we, in this country, used public money to build nearly 2,000 beautiful, lavish public pools in the 1930s and 1940s. But when Civil Rights activists pushed to integrate the pools in the 1960s, many cities chose to literally drain their public pools rather than integrate them. The drained-pool story helps explain how white Americans in these towns abandoned the idea of using collective action and collective money to produce collective goods. And so now we have fewer things that are furnished publicly that we can all enjoy that make for a great quality of life. Instead, we have private wealth, and only those with a lot of private wealth can enjoy those nice things.

Featured image: Terrance Wise (front left) and Bridget Hughes (right of Terrance) at a Stand Up KC rally. Courtesy of Stand Up KC (Facebook).

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.