\Many years ago, a young friend told me she was giving up politics. She’d been working for some time with one of the formations that emerged from the breakup of Students for a Democratic Society in the 1970’s, and was close to some of the organization’s local leaders. She seemed to be on a leadership trajectory herself. “Why are you quitting?” I asked.

“It’s because,” she said, “I’ve realized that all political work involves convincing people to do things they don’t want to do. Whether you’re handing them a leaflet they don’t want to read, or trying to get them to a demonstration they’d rather avoid, it’s basically about making them do things when they’d rather not. It’s uncomfortable and I hate it.”

That conversation has stayed with me all these years. I’ve remembered it on the many occasions I’ve found myself in uncomfortable conversations that I hated. Or more accurately, on those occasions when I hated having work up the energy to throw myself into those conversations — which often turned out not to be quite as painful as I’d imagined — even when I failed to convince someone to do something she didn’t want to.

There’s definitely a kernel of truth in what my friend said that day. Organizing absolutely requires talking to people who’d rather be left alone, about things they’d probably rather not think about. But I’d probably state it differently: organizing requires skillful conversations that help people to consider carefully what they do want and that show them how they can work with other people to get it. Organizing is not so much a practice of convincing people to act against their own interests and desires as it is one of motivating people to identify those interests and desires – and to go for them.

Of course, it’s not that simple. People’s interests and desires often conflict with each other, and with those of other people. People can, for example, want both cheap gas and to forestall climate change. Furthermore, most organizing campaigns begin from the assumption that the organizers know what policies (and in the case of revolutions, even what polities) will best meet those interests and desires. Even with the best of intentions, and the most transparent practice, there’s always – as my friend pointed out all those years ago – an element of coercion (social or moral, if not physical) involved.

Welcome to Washoe

I thought about that conversation a lot this fall. The 2018 midterm elections found me in Reno, Nevada, the center of Washoe county, working with Culinary Workers Local 226 in a campaign to elect a Democratic senator and governor. Spoiler alert: we not only won, we absolutely crushed it. Jacky Rosen will be Nevada’s new senator, and Steve Sisolak its governor. In a race considered too close to call up until the polls closed, Rosen won by 5 percentage points – 50% to 45%. Sisolak’s margin was a little smaller – 4% instead of 5%, but still decisive.

Local 226 is part of UNITE HERE, the hotel, casino and food-service workers union in North America. In spite of Nevada’s being a “right-to-work” state, UNITE HERE is a powerful political force there, representing over 57,000 workers, primarily located in the state’s two population centers – Las Vegas and Reno. That political strength is part of what guarantees members decent wages and benefits, and a voice at the table in Nevada and beyond.

Part of that strength resides in bringing voters out to the polls. This November Washoe, Reno’s home county, saw a 70% voter turnout – the highest midterm turnout in Nevada history. (By comparison, in 2014, the most recent previous midterm, only 52% of registered voters turned out.) In Clark county, site of Las Vegas, turnout was “only” 60% — still remarkably high for a midterm election.

The stakes couldn’t have been higher, for Nevada, the country, and even the world – insofar as Democratic victories challenge the Trump administration’s ever-consolidating power. Over the last 20 months the Trump administration has demonstrated the classic hallmarks of a fascist regime: racism, authoritarianism, and extreme nationalism. This rightward lurch comes in the disturbing context of growing anti-democratic movements internationally — from eastern Europe to Germany. Under these circumstances, many on the left, including UNITE HERE leadership, recognize the importance of challenging that administration on every terrain that’s available – whether it’s a picket line or a ballot box.

Was Jacky Rosen the ideal vessel for every left hope – especially in the realm of foreign affairs? No. But she supports raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour (it’s been stuck since 2009 at $7.25). She has visited the U.S.-Mexico border, investigating conditions at immigrant detention facilities. Unlike her opponent, Dean Heller. She’s committed to holding onto the health care rights Americans won under Obamacare.

Nevada’s voters had the opportunity to move the balance of power in the U.S. Senate. Rosen’s victory wasn’t to tip the Senate away from the Republicans, but it stung the GOP and consolidated Nevada’s status as a so-called “blue” state. For almost ten years, Washoe and Clark counties have put Nevada in the “blue state” column, but the margins have grown slimmer each year. Barack Obama beat John McCain in that state by almost 120,000 votes. Four years later, he beat Mitt Romney by a little less than 68,000. And in 2016, Clinton won Nevada, but only by 27,200 votes. Rosen’s margin was much higher than Clinton’s – almost 49,000 votes.

Voters also elected a Democratic governor in Nevada and gave control of both houses of the legislature to the Democrats. Control of state legislatures and governorships takes on national significance as the 2020 census approaches. According to the Gallup polling organization, since 2006, Republican party affiliation has hovered somewhere between 26 and 30% of the U.S. population. But gerrymandering congressional districts has allowed the party to hold 236 of a total 435 house seats. (Democrats hold 193, and six seats are presently vacant.) It’s after each decennial census that congressional districts get redrawn. The best chance of reclaiming congressional seats from Republican gerrymandering lies with winning as many statehouses as possible.

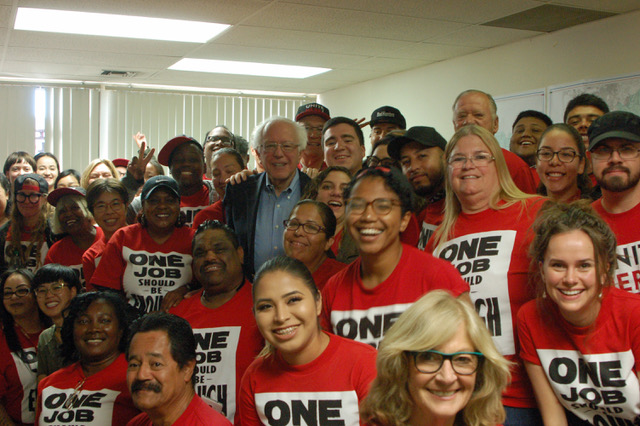

UNITE-HERE had at least two goals in this campaign. The first, of course, was to elect their candidates. Doing so furthers the interests of working people in general and the union’s national goals. These include guaranteeing the rights of immigrants, who make up much of the workforce in the hospitality sector; advancing the concept that “one job should be enough” for economic survival; and ensuring that all working people have access to adequate health care.

But the campaign had another purpose, one as important in its own way as winning the election. That was the development of organizers and leaders from the union’s rank-and-file. UNITE HERE emphasizes leadership among those who make up the majority of its members – immigrants, people of color, and women. They do this in a conscious and rigorous way. The three captains of our canvassing teams (the “leads” in union parlance), spent hours discussing the performance of each of the 35 canvassers. They encouraged quiet people to demonstrate the skills they were learning on the doors, and made space for people to present their own research about the election, or other political issues.

Getting people to do what they (don’t think) they want to: The three skills

In most morning meetings, the leads (like the canvassers, recruited from the union’s rank-and-file) – asked a few of the canvassers to demonstrate one of three crucial organizing skills: getting in the door, asking an agitational question, or telling a personal story. All three skills help canvassers make a genuine (if brief) connection with the stranger who opens the door when they knock. And all of them involve convincing people to do things they don’t want to.

“Getting in the door” means being able to claim a voter’s attention, even after the voter has said she’s busy, or not interested, or even disgusted by all the negative ads she’s seen on TV. Canvassers demonstrated approaches that worked for them: “I say, I can see you’re really busy, and I wouldn’t interrupt you, except that this is really important for our community. I’m a hotel housekeeper from Northern California spending two months away from my family, living in a hotel, to have a chance to talk with people like you.”

The purpose of “asking an agitational question” is to raise the emotional stakes of the conversation for the voters. This means paying attention to clues about their actual situation. It also means really listening to the answer to that question, and connecting that voter’s real concerns to the campaign. “Is the cost of living affecting your family?” a canvasser might ask in a less-affluent area. “Are you worried about how crowded your children’s schools are?” could be the question that gets the attention of a voter with a yard full of toys. Many Spanish-speakers responded vigorously to questions about how they feel about President Trump. Canvassers role play these conversations and discuss how to improve them.

“Telling a personal story” invites the voter to see the canvasser as a human being and to understand why their vote matters. Several mornings we listened with tears as one a canvasser told a true story from their own life. “When I was little my family was homeless,” one woman’s story began, “and I don’t want any other child to have to go through what I did.” Her generosity in exposing her life to her fellow campaigners – and to strangers on the doors – inspired us all to keep at it.

But it’s not enough to see the skills demonstrated. Every day the canvassers practice them in small groups, critiquing themselves and each other. The leads accompany them on the doors and debrief them on each conversation. This kind of training takes honesty and guts. There’s nothing nice about it.

But these are exactly the skills that union members will carry back to the job with them, ready to deploy when they are asking for something much more difficult than a vote. Most people don’t risk much when they go to the polls. It’s a different matter when the organizer is asking someone to risk her job by signing a union card.

Wide and deep

When I’ve worked on electoral campaigns with people from the nonprofit organizing world, I’ve found they’re often very frustrated with the quality of contacts they can have in the short time they have talking with each voter. In community organizing the goal is to make a deep connection with people who are potential or actual community leaders. Often this takes multiple conversations and visits to people’s homes, and involves a process of opening up on both sides. You don’t have forever, but time is on your side.

Electoral organizing, by contrast, is often described as going wide, but not deep. You have to touch as many people as possible within an inelastic timeframe, with the single goal of getting them to vote your way in a specific election. It’s all about the numbers. That’s why electoral organizing can be unsatisfying; even when you win an important election, it can feel like you haven’t built anything lasting. The day after the election, it often seems that the organization you built is as easily dismantled as the campaign office where you’ve lived for the last few months. Even when community organizations participate in elections, they often find it difficult to consolidate their relationships with their campaign volunteers, let alone the actual voters they’ve met.

UNITE HERE’s electoral campaigns have two key assets – their organizing upgrade, if you will – that most nonprofits lack. First, they have the resources (from their members’ hard-earned dues) to pay fulltime organizers long enough to get good at what they do. Second, they have figured out how to use elections as a training arena for the people who are building the union itself. The skills union members learn and practice in a well-run election are highly transferrable to union recognition struggles, contract fights, and campaigns to involve a wider community in a strike or boycott.

And, yeah, they involve hard conversations people don’t know they want to have.