A U.S. nuclear submarine collided head-on with an unknown object in the South China Sea on Oct. 2, 2021, prompting the dispatch of a U.S. spy plane whose purpose was to detect radioactive debris. It took the Navy five days to release a terse statement, prompting anger from Chinese defense officials who were fearful of possible nuclear contamination of the area.

According to peace activist John V. Walsh, writing in the Asia Times, Chinese defense spokesperson Tan Kefei chastised the United States: “Such an irresponsible approach, cover-up [and] lack of transparency … can easily lead to misunderstandings and misjudgments. China and the neighboring countries in the South China Sea have to question the truth of the incident and the intentions behind it.”

History tells us wars often start with incidents like this.

It’s a dangerous game nations play when warships are in proximity. In 1964, a conflict in the Gulf of Tonkin, also in the South China Sea, was the excuse the United States needed to escalate the war in Vietnam. The jingoistic response that ensued killed more than three million Americans and Vietnamese (most of them Vietnamese). Whether incidents of conflict are real, perceived, or fabricated, we must be clear — the bourgeoisie will use any conflict at its disposal to whip up hysteria. In the end, it is the working class and all oppressed people in these countries who pay the price.

The breakdown of the neoliberal consensus

What is causing these increased tensions that came to a head in the underwater maneuvers in the South China Sea? From the time Richard Nixon extended an olive branch to the People’s Republic of China until the economic crisis of 2008, there was little tension between the two countries. Writing for The Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, Tobita Chow, Director of Justice is Global and an editor of Organizing Upgrade, said this:

“In the two decades leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis, the U.S. and China established a stable, symbiotic relationship founded on neoliberal patterns of growth and legitimacy. The neoliberal accommodation strongly served elite economic interests in both countries: Chinese businesses received investment, access to advanced technology, and a huge export market, while American businesses exploited cheap factory labor and gained entry to the world’s fastest-growing market. Profit and corruption flourished as local and transnational capital collaborated to destroy the power of labor in both countries.”

Chow explains that it was the differing economic approaches after 2008 that caused a crisis of overproduction. China’s massive stimulus spending kept the world’s economy from totally collapsing during the Great Recession. But western capital’s austerity measures, particularly in Europe, suppressed consumer demand.

Chow further states, ” In both countries, vilifying the other became increasingly attractive to channel public anger into nationalism against a foreign threat, in hopes of imposing unity on the fractious population and mobilizing the nation for competition within the newly zero-sum global environment. Thus, both sides have failed to address the root causes of economic and political turbulence and are instead only deepening the crisis.”

But the complications of the US-China relationship are deeper than the breakdown of their long-standing economic cooperation. There has been a profound interpenetration of the two economies. This is about more than trade. It is about investments, the spread of multinational corporations, the purchase of bonds, etc. This has resulted in a profound contradiction between mutual economic interdependence, on the one hand, and state competition on the other. The factors involved in state competition include race and an effort by the ruling elites in both countries to suppress domestic struggle through the focus on an alleged external opponent. As we saw also with Japan in the 1970s and ‘80s, competition from Asia is portrayed through a racial lens, tinged with the myth of the “yellow peril.”

What also must be understood is that the United States, as the longtime dominant economic and military power on the planet, has been embroiled in an on-going internal battle over the changing nature of global capitalism and the implications at the level of the state. Since the 1970s, representatives of a transnational capitalist class have clashed with, and sometimes collaborated with, domestic capitalist classes. Crudely put, the question now is whether the United States will cooperate with other real and imaginary capitalist competitors in the interest of global capitalist hegemony, or insist that it is the way of the USA, or it is no way at all?

Competition equals instability

And this increased competition between global superpowers threatens an already unstable world. The global economy that arose during the neoliberal consensus of the past 40-plus years has been disastrous for working people, small farmers, and fishermen around the world. Millions every year are thrust into poverty. As more and more fossil fuels are burned, the resulting environmental degradation causes mass migration as people search for a way to live.

We’ve already seen under Donald Trump’s administration the racism toward Asian-Americans that boiled over with violent consequences. Right-wing thugs and others took Trump’s anti-China rhetoric as license to engage in random street attacks. President Biden has cooled the overt racism but has continued the economic sanctions and anti-China rhetoric that have increased tensions with Beijing. As long as U.S. submarines patrol the South China Sea, we are always one accident away from war breaking out.

A major underlying source of tension in the South China Sea has been the status of the island of Taiwan, where Chinese opponents of the socialist revolution retreated in 1949. This is a complex subject that requires an article of its own. But the most relevant point here is that according to the Wall Street Journal, a U.S. special-operations unit and a contingent of Marines have recently been secretly operating in Taiwan to train military forces. We must demand that President Biden suspend this military operation and uphold the prior agreements signed in 1972 and 1979 that set the One China Policy.

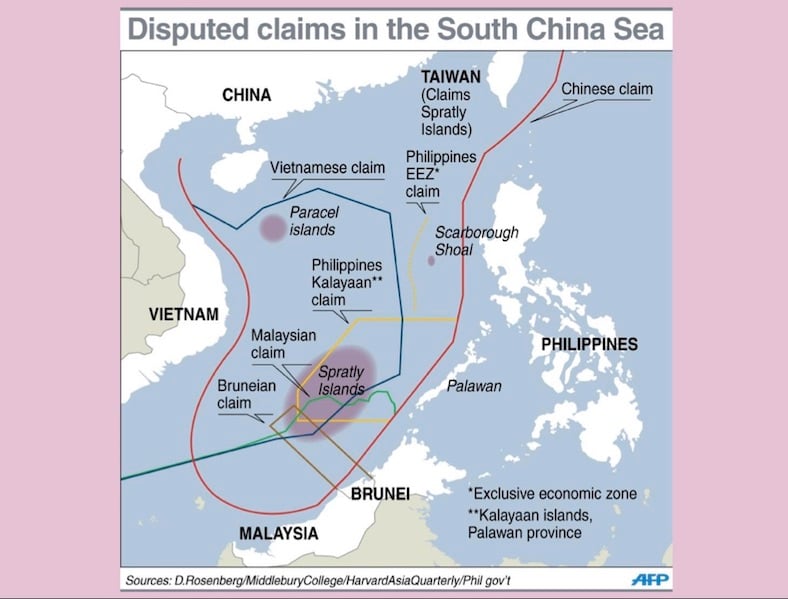

The threatening military presence of the United States intensifies the decades-long tensions in the South China Sea. Walden Bello, the national chair of Laban ng Masa and international adjunct professor of sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton, says China (and the) US must both stop destabilization. He rightly points out that China’s claim of 90% of the South China Sea is illegal and has no basis in international law. There are five other countries that border the South China Sea and 60% of the world’s shipping passes through it.

The disputes in the region between China, Vietnam, The Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and the island of Taiwan should be settled through diplomatic means and treaties. Besides shipping lanes there are the questions of fishing rights, oil and natural gas exploration, and the ecology of the sea. China’s practice of building artificial reefs and islands and using those to expand its borders and claims to water rights around the islands in the South China Sea (called the East Sea by Vietnam) is historical absurdity. In actuality, only three of the 250 islands have fresh water. Archaeological evidence, in fact, has shown that the islands were settled 6,000 years ago, by Vietnamese.

Setting the state to resolve disputes

The military maneuvers of the U.S., both overt and covert, must stop. The U.S. left has an international duty to demand this of the government. The withdrawal of U.S. warships is a necessity for stability in the region.

The countries in the region could make a joint declaration to share oil resources that are abundant in the South China Sea or, better yet, renounce the high cost and ecological damage of recovering oil by leaving it in the ground and work together to develop alternative energies. (This article was written before the U.S. and China announced at the United Nations Climate Conference in Glasgow that they would discuss a climate change cooperation agreement. Though that announcement was vague, it could provide new opportunities to push for greater collaboration.)

Also, an interregional fishing commission to regulate fishing in the South China Sea could be negotiated. Fishing has been a way of life for centuries in all the countries of the region. A commission could create an exclusive economic zone that helps manage this valuable resource and ensure a sustainable ecosystem.

Most countries abide by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The countries of the region together could designate an international shipping lane through the area. Although the United States is one of the countries that does not abide by UNCLOS, it uses the excuse of “freedom of navigation” to patrol the area. An agreed upon shipping lane could delegitimize this practice of the US.

In addition, the US should sign onto UNCLOS and honor any agreements crafted by countries in the region.

Much of the tension in the world today can be tied to the breakdown of the neoliberal order. As profits are squeezed, the capitalist class often will whip up nationalism among the people and use them as cannon fodder if the need arises. The rise of nationalism must be opposed by an internationalism that values the interest of all working people in every country. Peace and cooperation among nations is our demand.